Briefly, this evaluation was designed to address the following three questions:

- What are the changes in measurable health outcomes for mothers and newborns, including changes in maternal stress, well-being and satisfaction with birth experience?

- Is this model financially viable and sustainable with skilled and satisfied health care providers?

- Does a local maternity care center change the community in measurable ways?

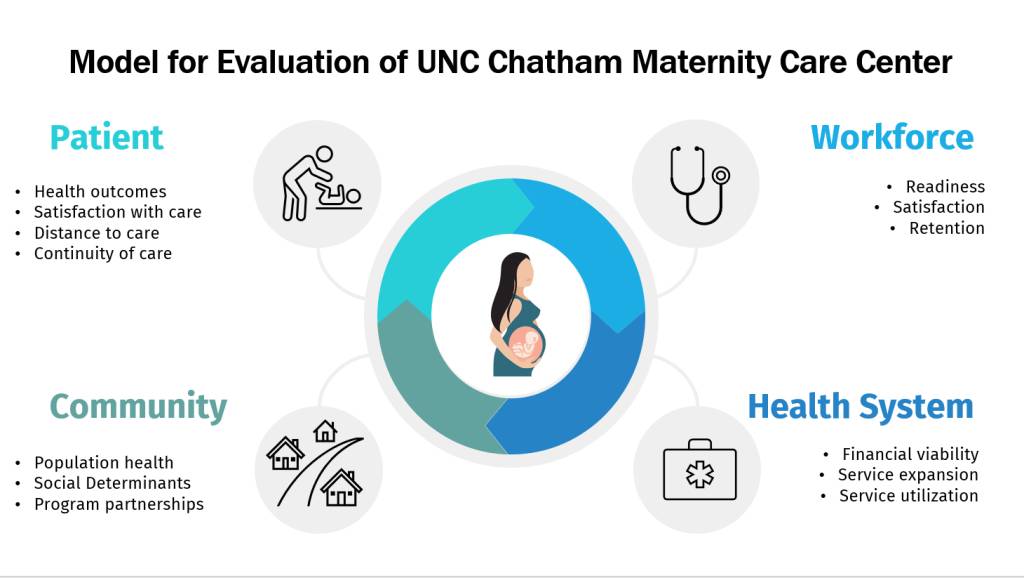

As illustrated in Figure 1, the evaluation is designed to gather data across four identified areas of interest: patients, workforce, healthcare system and community.

As with any evaluation, there have been lessons learned:

Responsiveness to COVID-19: The Chatham Maternity Care Center opened during the COVID pandemic, at a time when all healthcare systems were stretched. The hospital and the maternity care center have had to respond to these complexities in ways that limited their ability to publicize the opening and develop relationships with local collaborators. COVID affected protocols around patient visitors and touring of the unit as well as increasing healthcare worker burdens which led to staffing shortages.

As far as our evaluation is concerned, it will be difficult to untangle the effect of the pandemic on many of the measures being collected. For example, was the initial lower patient volume due to the reduced visibility of the unit because it opened during the pandemic, or a lack of adequate trust or desirability of the unit to local families? Is the turnover in RN-nursing staff a product of the nationwide nursing shortage or due to other aspects of the work environment in a rural setting?

Complexity of healthcare finances: The Critical Access Hospital status and affiliation with a university hospital brings both benefits and challenges. Financial losses were anticipated in the first year after the Maternity Care Center opened, but the high proportion of uninsured patients, the low Medicaid reimbursement rates for deliveries, and the high staffing costs associated with a university system created a greater loss than was initially anticipated. Leaders from across the hospital system are working to shift the model enough to bring down costs and to understand how the unit at Chatham Hospital financially benefits the hospital system as a whole.

Importance of qualitative data: Quantitative data are the cornerstones of our evaluation; however, the qualitative data have been critical in defining the story behind the unit. There is a feeling to the work that can’t be captured with numbers. For example, we know that the cesarean section rates are remarkably low but to hear that a father was proactively invited to cut the umbilical cord, even though his baby was born by cesarean section, builds a picture of high-touch care throughout the surgical procedure. We know that most patients live very close to the hospital but when we hear that a doctor played her own music for a patient during delivery based on their shared musical tastes, or that a nurse collected furniture from the staff for a patient who confided that she didn’t have any, we get a sense of the unit truly being a part of and supporting the community.

Rural communities need more than a place to give birth, they need to know that the healthcare system is there for them. They need access to quality care. And they need an equity-focused approach that brings non-judgmental care into the places where they live and work.

Our team of evaluators is excited to continue our work with The Duke Endowment tracking both the challenges and successes of the promising Chatham MCC model to improve the landscape of rural maternity care across the United States.

Martha Carlough, Ellen Chetwynd and Katie Wouk of the University of North Carolina are the primary researchers on the UNC Chatham evaluation project.